July 20, 2015

Where were you?

I was living in Palo Alto at the time. I was working in technology. When I saw, the headline, “PayPal Spinoff Day has Arrived,” I shrugged. I even gave the company mental side-eye:

➡️ “Isn’t that the company inside eBay who hasn’t done anything innovative in years?”

➡️ “Does anyone even use PayPal outside of eBay?”

➡️ “That company is 20 years-old. It’s a dinosaur.”

In fact, what I remembered the most was a clip of Elon Musk talking about PayPal. The prior weekend I had been watching a 1-hour interview of him. To me, as a product person, Elon said amongst the most offensive things one could say about a company. “If you look at the product plan I wrote in 2000… there’s hardly any difference.”

He essentially claims they were not moving fast enough or innovating. Like many others in the Valley, I had no attention for a company that I perceived as not innovative. Years of operating under the eBay parent had led to the brand losing much of its cultural cachet amongst tech workers.

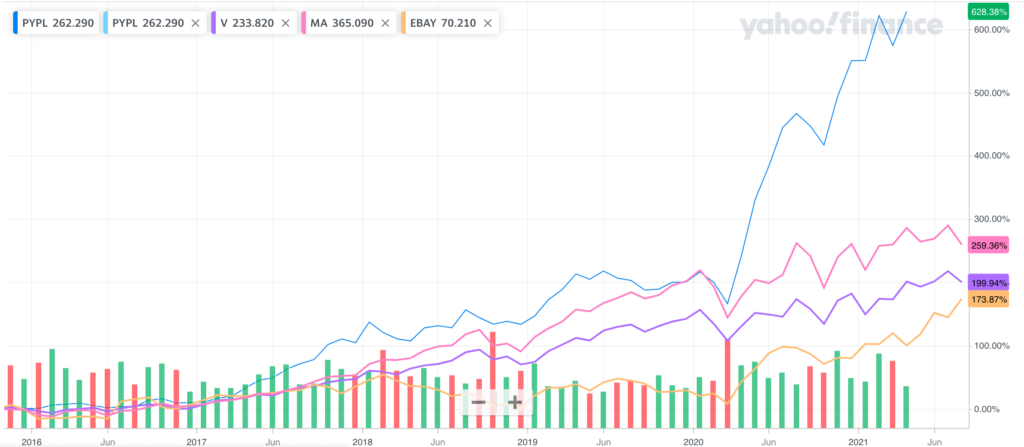

But it turns out I was wrong. Badly. You may have been following along the story, nodding your head as well. Perhaps the litmus test is, did you buy the stock? If not, you too were wrong. PayPal has had an absolutely remarkable run since its spin-off. The stock price is now 7x. This is far faster enterprise value growth than its former parent, eBay. It is also far faster even than payment company rivals Visa and Mastercard:

How did PayPal grow its enterprise value so tremendously? How has it reached $327B in market cap, 6.5x its former parent eBay? That is just $24B (7%) behind Mastercard.

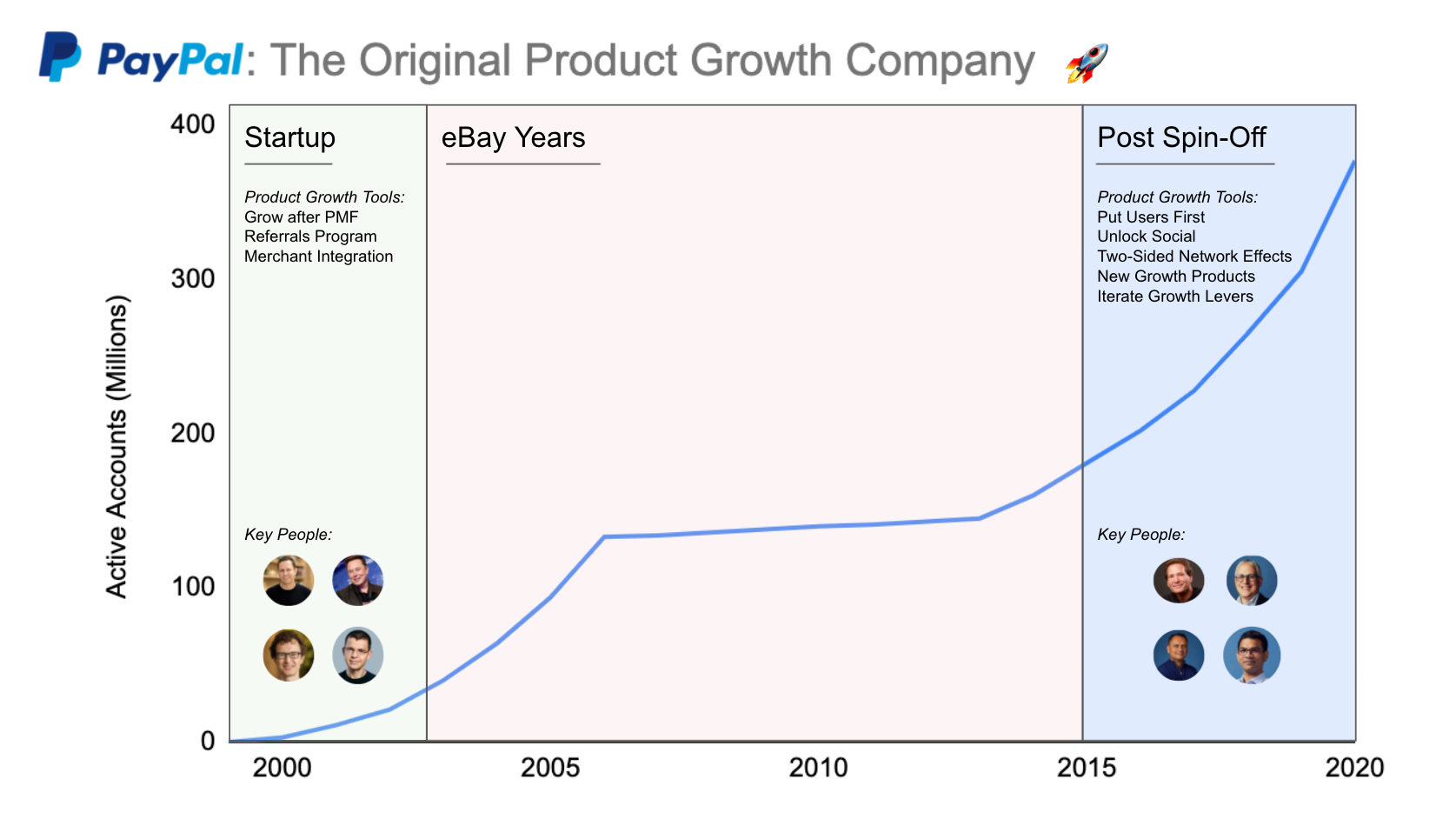

PayPal is the original product growth company. This DNA has lived in on the company as it evolved and accelerated since the spin-off. Let’s walk through a historical story of the company to take away 8 product growth lessons that should be foundational for any product growth professional.

Phase 1: Product Growth DNA – Pre-eBay 🧬

1998

Just a year after graduating from his Computer Science undergrad, Max Levchin came to Silicon Valley to start a company. A man searching for an idea, Max was exactly the right combination of curious and ambitious to make one of the most consequential chance encounters in the world happen. One afternoon, he attended an obscure financial talk at Stanford University. There were only 6 people in the room. Max was one of 5 other people listening to Peter Thiel talk that day. Peter clearly was not as famous as he is now, then.

After the talk, Max engaged Peter. He wanted to start a company. Specifically, he was interested in cryptography. Peter was also interested in starting an internet company. Peter was running a small investment firm at the time, 31 years old. He had seen many friends experience the assymetric rewards of a startup. Together, the two teamed up.

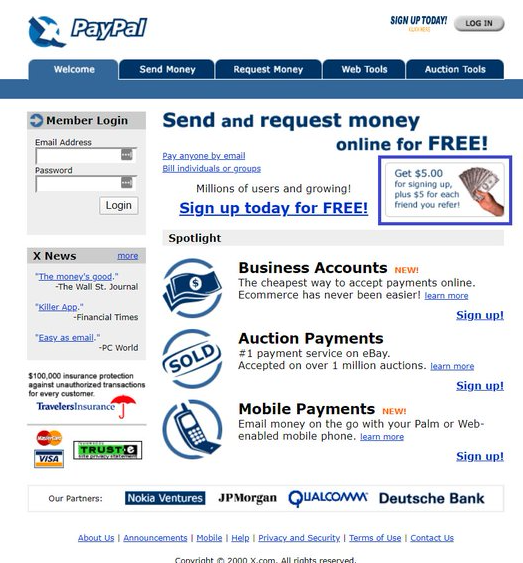

They combined Max’s interest in crypto and Peter’s interest in financial markets. Together with Luke Nosek, the three original co-founders came together to start a digital wallet company. At the time, it was named Cofinity.

PayPal was born.

Lesson 1: Only growing after PMF

The trio created FieldLink, a digital wallet and peer to peer payment facility for PDAs. Unfortunately, there were two problems with this business. First, the market for PDAs was not large. Second, without a network of people to send and receive money, the digital wallet did not solve a core user problem. Simply, they did not have product market fit.

This is where we encounter the first product growth lesson from the history of PayPal. Do not grow a product without the right characteristics: a fit with user needs, and a sufficiently large market. The young company did not continue to toil in obscurity with FieldLink. They pivoted.

In fact, they found the idea that would propel them for decades to come. The company shifted to a web checkout and email based digital wallet. This product had both a bigger market and better product market fit. It solved an increasingly universal customer job to be done: making sending and receiving money online safe and secure.

It was only at this point, after these crucial criteria had been met, that the company began to write the playbook for product growth. Let’s continue down history to learn about it.

1999

Lesson 2: (The first) referrals program

PayPal launched the first (known) give $20, get $20 online consumer product referral program. This was a hype cycle technology trigger moment. Courtesy of PayPal’s head of marketing at the time, Luke Nosek.

The referrals program saw steady success in the first few months. It was useful. It allowed you to have a source to send and receive money online with just an e-mail address. Plus, you started out with $20. As early adopters began to see the immediate needs this problem addressed, they wanted to pay and receive money with their friends, using PayPal. Because of the inherently social nature of sending and receiving money, the referrals channel had perfect fit as a growth lever for the product.

The third month, the referrals channel hit escape velocity. It began growing exponentially. The program was compounding 5-6% a day.

This is the second major lesson in product growth from the PayPal case study: referrals channels tuned correctly can generate exponential growth. As the LTV of acquired users declined, PayPal reduced the incentives. Give $20, get $20 becomes give $10, get $10. Then give $5, get $5.

Asked years later, Peter Thiel estimated the company spent $60-70M on the program in its first years of existence. Given incentive decreases over time, I estimate it generated 5-6M new active transactors on PayPal. That is the type of scale product growth professionals salivate over.

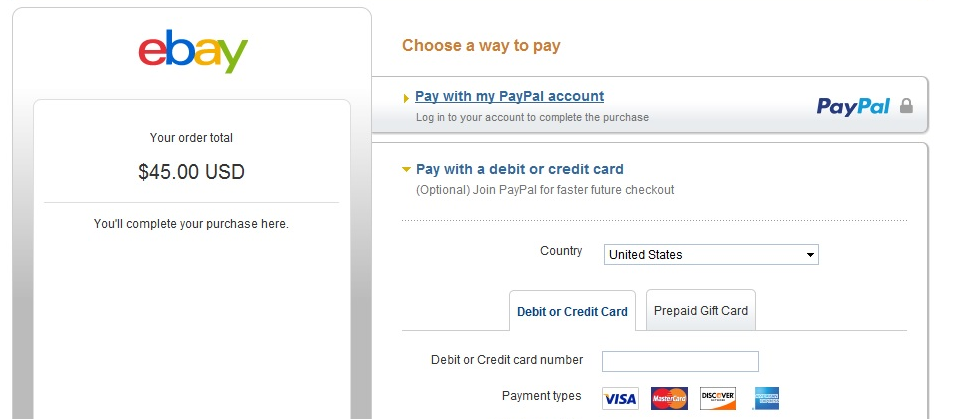

Lesson 3: (The first) big merchant integration

At this point in PayPal’s history, we also encounter its second big (consumer) growth lever: a big merchant integration. You see, at this point in the internet ecosystem, eBay was the king of e-commerce. Amazon was not the everything store. Shopify and Etsy were not around for small businesses. A great deal of e-commerce was going through eBay.

PayPal set a product/engineering team to build an integration with eBay. In short order, the PayPal button was driving more volume than eBay’s own in-house platform.

Now, dedicated product growth teams supporting merchant integrations are a tried-and-true tactic for all manner of FinTech companies (Square, Klarna, Stripe, to name a few). But PayPal was the first to demonstrate this in a major way.

2000

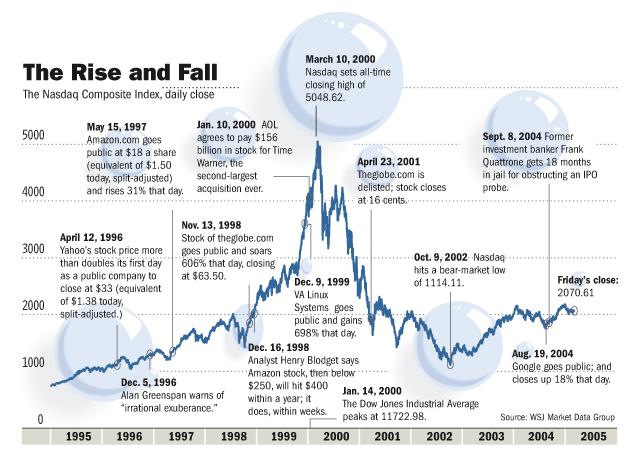

As PayPal continued to zoom to greater and greater heights with its innovative use of the referrals and merchant integration product growth levers, the company also faced increased competition.

One of these foes was X.com, the digital bank startup of Elon Musk. In March 2000, with both companies hemorrhaging cash, they merged. Elon assumed the CEO role. In his now famous Elon fashion, things were intense inside the company. Everything moved at lightning pace.

Left and right, PayPal innovated on fraud, payments, and wallets. The company launched merchant accounts. This turned out to be one of the company’s most important decisions in its history. It began to holistically pursue both consumer and merchant accounts. Peter Thiel actually left.

After not having taken any vacation since his wedding, Elon finally took two weeks of vacation in September. Unfortunately, things did not go well at the company when Elon was away. Elon returned to a management team that wanted him out of the CEO seat. By October, Peter Thiel was back, and in the CEO seat.

Meanwhile, at the Federal Reserve, chair Alan Greenspan raised interest rates several times. March 10, 2000, the NASDAQ peaked. From there, the world saw a market downturn that lasted until October 9, 2002.

2001

Despite the context of the internet stock bubble bursting, PayPal kept on growing its active users, transaction, volume, and market capitalization.

Then, September 11th happened. The world was shocked. Companies stopped IPO’ing. NASDAQ is in New York City. Ground zero for the attacks.

2002

Nevertheless, the PayPal team persevered. The company was the first company to IPO post 9/11. The IPO was a smashing success. Shares rose 50%.

But, the merchant integration product growth strategy perhaps proved a bit “too successful” for the 4 year-old startup. July 8, less than a year after IPO, PayPal was acquired by eBay for $1.5B. By October, PayPal was a part of eBay.

Phase 2: The eBay Years 🐌

Under the ownership of eBay, PayPal spent 13 years moving closer with its parent. While legions of bright people worked at the company, its product growth stagnated. The team focused on enhancing the checkout experience at eBay. This only drove active accounts higher linearly. The company lacked a sharp focus on growing its payments business.

2007

One of the most significant things to happen to PayPal during the eBay years was in 2007. Fortune Magazine published the famous piece, The PayPal Mafia. What was until that point a fact known in Silicon Valley become national news.

The continued success of the PayPal mafia members since 2007 has resulted in only continued growth in knowledge about them. In fact, most of my editors for this article had heard of PayPal Mafia members, but could not name the current CEO of PayPal. He is an important character in this story. We will meet him soon.

During the eBay years, it is worth mentioning that the company did make some valuable and strategic acquisitions.

- January 2008: Fraud Sciences, risk & fraud management

- November 2008: Bill Me Later, with over 9000 online merchants

- September 2013: Braintree, who also owned Venmo

These companies end up playing a key part in PayPal’s product growth.

2014

On September 30, 2014, everything for PayPal changed. The leadership at eBay tapped a seasoned technology executive, Dan Schulman. Dan had already taken two companies public. Under his tenure, Priceline.com not only IPO’d, but also grew its revenues from $20 million to $1 billion. He then repeated the feat with Virgin Mobile, having been hand recruited by Richard Branson to the founding team himself. So, it was fair to say that the eBay brass had high hopes for their new executive. But, no one could have quite predicted the impact he would have.

2015

Less than a year after taking the reins, Dan successfully led his third company public. On July 20th, he led the spin-off of PayPal from eBay. PayPal’s market cap immediately surpassed its parent.

Phase 3: Post Spin-Off ↗️

2016

Lesson 4: Putting the User First

In 2016, PayPal made a huge change to its entire strategy. After 18 years of existence, it stopped directing customers to their low-cost instrument on file. Instead, they put the user first. They started giving customers choice, allowing them to choose what instrument they wanted to pay with.

This meant PayPal was going to get less per transaction, but consumer’s payment needs would be met better. The results have been great for PayPal. Users have returned the goodwill in the form of higher loyalty. They transact more with PayPal, increasing its transaction volume. This is the fourth critical product growth insight from PayPal.

You may be able to trade-off the short-term for the long-term by putting the user first. Putting users first is a product growth lever almost any company in any industry can pull.

2017

Lesson 5: Unlocking Social (with Venmo)

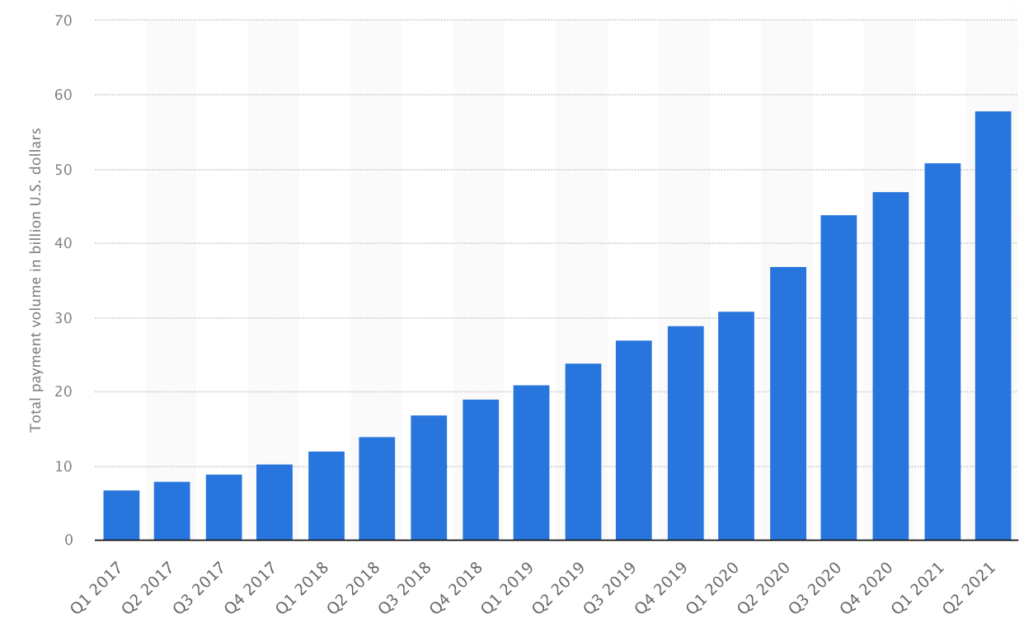

Since 2017, PayPal has unlocked social in Venmo. The transaction volume has grown every single quarter, from $6.8B to $58B. This growth is absolutely tremendous:

Venmo is not popular because its peer to peer payment technology is the best. Venmo is popular because it plugs into social networks. It is a social payment experience. This is the fifth critical product growth lever from the PayPal case study: unlock social.

This is more than just social referrals programs. By making the social feed a core part of why users use Venmo, PayPal has created an engagement hook beyond the basic utility of peer-to-peer payments. Gaming companies like Roblox and Fortnite have been using this product growth lever for years. People stick around more when they are using your product with friends.

Building out social loops and experiences like Venmo is now a tried-and-true product growth lever. PayPal has just continued to scale this lever better than almost anyone else in FinTech.

2018

Lesson 6: Building Two-Sided Network Effects

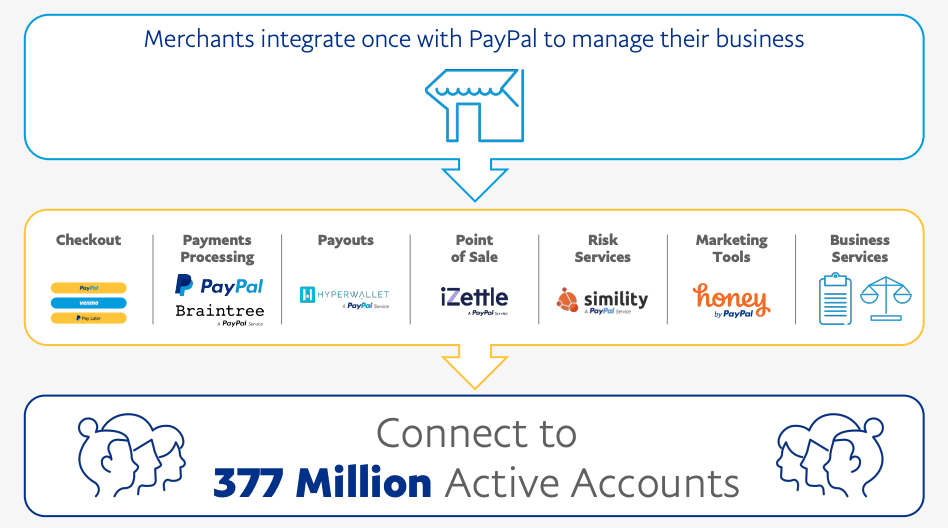

Another critical product growth strategy that the company has been doubling down on is building two-sided network effects. Each group feeds the other. More consumers make PayPal more attractive to merchants. More merchants make it more attractive to consumers. Acquiring many merchants and consumers adds not one, but two, moats for competitors.

The company has always been pursuing this lever. But it really double clicked into this area starting in 2018. June 21, it acquired Simility for risk services. September 20, it acquired iZettle for point of sale. November 15, it completed the acquisition of Hyperwallet for payouts. [The next year, November 20, 2019, the company also acquired Honey.] All these acquisitions work together. They provide a great deal more value to PayPal’s two-sided network:

This is the sixth important product growth lesson from PayPal. Build two-sided network effects to strengthen your moat. You can even do so with acquisitions. The moat is why marketplace businesses trade at such high market cap/ sales multiples.

Lesson 7: Building New Growth Products

Under eBay, as late as 2014, PayPal had a limited vision for its products. Its “growth strategy,” if one can call it that, included platitudes like “always at the centre of the next innovation” in payments. But now the company is thinking much more holistically about consumer finance. It is building new growth products. Just look at the app now:

This is all part of PayPal’s strategy to solve the consumer pain point that we don’t want 40-50 apps with 40-50 different passwords. So, the company white labels new financial products in partnership with banks to bring them under a PayPal brand login. Whether it’s crypto or buy now, pay later, these products have huge markets. Even if PayPal does not become a winner in each market, it can really help solve needs of its users. If you do not need the best crypto access or savings account, having it in your PayPal login is valuable.

This is the seventh product growth lesson of the PayPal case study: build new products adjacent to your main one. Critically, these products are within a framework that helps other products – not siloed. As long as the new growth products solve core problems for your existing users, they can help the stickiness of both groups of products. In fact, 50% of PayPal’s crypto users login everyday! This engagement is much stickier than other PayPal features. The log-in exposure from crypto helps those less frequently engaged with features.

2021+

Lesson 8: Still Iterating on Growth Levers

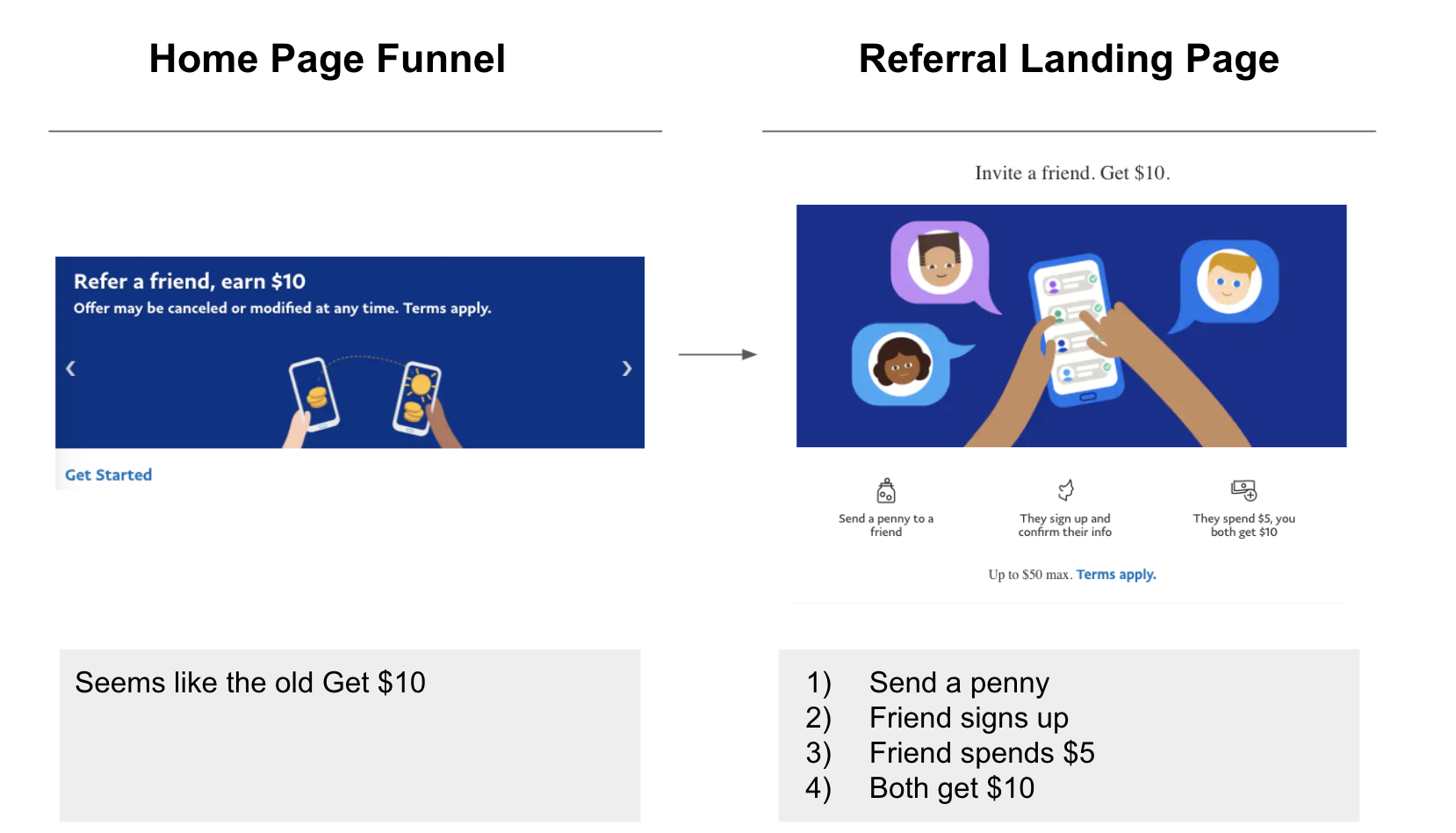

This brings us to the present day. PayPal does not rest on its laurels. The six growth levers we covered – referrals, merchant integration, user first, social, two-sided networks, and new growth products – are continuously seeing investment from PayPal. Look at its latest referrals program:

That is the eighth and final lesson from the PayPal case study: product growth is not “set it and forget it.” Once you pursue one of the growth levers we learned here, you should staff a product team with engineers, product manager, and analyst to continue to iterate on the lever.

Learning from PayPal: Product Growth Takeaways

In studying the history of PayPal, we have encountered nearly the entire core toolkit of product growth professionals: solving user needs, building two-sided network effects, unlocking social, referrals, putting the user first, and new growth products. We have now gotten to tactically feel these strategies applied at a real company. Importantly, we have also gotten to learn when to apply this toolkit: after PMF. We have also learned how vital it is to continue to iterate on each lever.

In future posts, we’ll dig more into these toolkits. We’ll generalize tactics. We’ll study more companies’ cases. To join me, subscribe to the Product Growth email newsletter. Or review my archive.

Note: Although I work at Affirm, all thoughts in this post are my own. I am just a humble newsletter writer, commenting on product growth lessons after research.